|

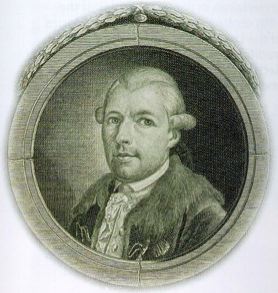

| Adam Weishaupt, founder of the Bavarian Illuminati |

As I write this blog post, it is Friday, May 1st. The first day of May is a date that means different things to different people: to some, it is just

a calendar date; to others, a day for folk celebrations of spring and summer.

But May the First is also the anniversary of the founding of an organization

that has proved to be even more famous in its death than during its life, a

group about which more falsehood has been published than perhaps any other. To some, the group is a historical footnote. To others, it is the hidden power behind every throne,

even today—and supposedly the secret masters of the Masonic fraternity.

So it is that today’s blog post is, if not in honor, in

acknowledgement of the establishment of that fascinating and sinister

organization: The Bavarian Illuminati, founded on this date in the year 1776.

The group was revolutionary in origin, seeking to overthrow

the power of aristocracy and monarchy in favor of a form of government

resembling democracy—largely through assassination, or so they planned. The group also sought to overthrow the political and

social power of the Roman Catholic Church, in favor of instituting reason and

logic as principles by which to govern the world and educate humankind.

The Illuminati were originally known as Perfectabilists,

reflecting their belief that people could achieve a sort of perfection through

rigorous devotion to reason and logic, rather than through supernatural means

(such as the atonement of Christ).

The Illuminati was a truly “secret society,” in that it

tried to keep its very existence secret. The Illuminati infiltrated dozens of Masonic lodges in central Europe,

where they sought to recruit members whom they hoped to lead, through a system

of ritual degree ceremonies resembling Masonry, from a position of belief in

God (a requirement for membership in regular Freemasonry) to a position of

atheism, devoted to the overthrow of monarchy and church. The leadership of the

group believed that, to further this endeavor, any means were justified,

including political assassination.

To understand the Bavarian Illuminati, it is important to

understand the political context of their times. American-style democracy had

not been invented, and people throughout central Europe in particular were

ruled by absolute monarchs who essentially held power of life and death over

the people they governed. Dissent was crushed. In addition, the major church of

the period held a significant degree of political power; in religious matters

as well as political ones, dissent was not tolerated. The emphasis that the

Illuminati placed on freedom of thought and expression was very appealing to

some people, including even members of the aristocracy, and German literary

figures such as Goethe and Herder; reportedly, the Illuminati reached a

membership of about 2,000 during the decade or so of its existence.

The Illuminati were strong on rhetoric, but weak on action.

They assassinated no one, despite their “ends justify the means” ethics.

However, when their aims became known to the governing authorities, they were

crushed by the rulers of several countries, beginning in 1784. By the early

1790s, for all practical purposes the Illuminati had ceased to exist.

And it was then, after the group known as the Illuminati

died, that it really got to work.

The Strange Afterlife of the Illuminati

The late 18th and early 19th centuries were a time of

monumental social change—which meant, not only positive changes like the rise

of democracy, but also social disruption that was experienced very negatively

by many thousands of people. In the mid-18th century, before the Revolutionary

War, many American colonists considered themselves loyal to the British crown;

after the war, thousands of these people left their homes and businesses and moved, to Canada, England, and elsewhere,

leaving behind thousands of relatives and friends who were quite unhappy about

losing their connections.

Loyalists and their

relatives were not the only people who were less than happy with the American

Revolution. A lot of clergy of “established” churches (that is, churches

formerly supported by the government) were troubled by the withdrawal of financial

support, which they took to be an attempt to undermine religion generally.

Overall, many people in the new United States—echoing even greater numbers of

people in Europe, still under the power of Crown and Church—were troubled by

the direction that the new Republic was taking, in denying aristocrats and

clergy their former privileged position in government.

Thus arose the rumor

that the inspiration of the new Republic was actually the Illuminati. In the

1790s and thereafter, American clergy preached sermons from their pulpits

against the supposed influence of the Illuminati in the United States. Books

originally published in Europe alleging the ongoing Illuminist conspiracy, such

as John Robison’s Proofs of a Conspiracy (1797), were widely

read in the United States, and fanned the flames of what amounted to hysteria.

The first novel by the first American to make his living as a novelist, Charles

Brockden Brown’s Wieland (and his unfinished Memoirs of

Carwin the Biloquist) involved the role of an Illuminati agent in America

impersonating the voice of God to convince a man to murder his wife and

children. In the real world, Thomas Jefferson himself had to answer charges

that he was an Illuminatus.

It gets better. The

1970s-era Illuminatus! trilogy of novels, by Robert Shea and

Robert Anton Wilson (two editors at Playboy magazine), put forth the rumor that Adam Weishaupt left Europe,

came to the United States, murdered George Washington and actually took

Washington’s place as first President of the U.S. Incredibly enough, there are

those who believe today that this actually happened!

No, it gets even better.

Current proponents of way-out-on-the-fringe conspiracy theories—people like Jim

Marrs, Texe Marrs, and David Icke—say that the modern world is under the secret

control of the Illuminati even today. For Jim Marrs, the Illuminati are

political powers; for Texe Marrs, they are Satanists; for David Icke, they are

reptilian space aliens. (No, I am not making this up.) All

of this is furthered by the appropriation of the name and supposed symbolism of

the Illuminati by some current entertainers, who use it to give themselves the

sheen of power that attaches to the paranoid version of the Illuminist legend.

The Illuminati have been the scapegoat of American politics

(and, to some extent, European politics) for the last 200 years. The horrific

excesses of the French Revolution were blamed on the Illuminati. The

suppression of American Freemasonry in the first half of the 19th century was,

in part, based on fear of the Illuminati. In our day, particularly since the

middle of the 20th century, the Illuminati have been blamed for everything from

AIDS and the Great Recession to the flouridation of public drinking water.

(Google “Illuminati” and you'll see what I mean.)

And it’s all a pile of hooey. The Illuminati died out in the

late 18th century. They are kept ‘alive’ in the minds of ignorant people today

because we, as a society, have done such a poor job of teaching critical

thinking skills.

There is a cost to all this wild-eyed attention given to the

Version Two-Point-Paranoid of the Illuminati. By projecting all of society’s

problems onto some supposed All-Powerful Others, people perpetuate the myth

that they themselves are not responsible, either for creating society’s

problems, maintaining them, or trying to solve them. Today, the myth of the

Illuminati lets people off the hook for taking charge—of their lives, of the

political process, of their own destinies.

I hope that my Masonic brothers will spread the truth about

the Illuminati, and lead the way in following the Enlightenment-era maxim that

should guide all Masons, and all people, “Follow Reason,” in evaluating

conspiracy theories, and in approaching the very real problems that our society

faces.

- - -

I invite you to become a “follower” of this blog through the

box in the upper-right hand corner. I also invite you to subscribe to the RSS

feed for this blog.

Visit the “That Freemason Mark” page on Facebook.

Visit MarkKoltko-Rivera’s website.

[The image of Adam Weishaupt was obtained

through Wikipedia. The artist is unknown, but the image is in the public

domain.]

(Copyright 2015 Mark E. Koltko-Rivera. All Rights

Reserved.)